Cinematic Paintings by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

⏱ 8 min

As a result of lockdown, all cinemas have been closed and thus, it has been so long since I was last able to attend, making it feel like a distant memory. Likewise, with galleries, it was two months ago when I last saw art in person at Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s Tate Britain exhibition. Luckily, the new announcements regarding the Tier 4 restrictions in the UK mean that the galleries will be back open very soon and when they do, the enjoyment of consuming art in person will reconvene! As will the act of going to the cinema and screening a film in the widespan environment, instead of streaming films on Netflix or Amazon Prime. However, before that moment does arise, I wanted to draw a focus towards an interpretation and way of seeing the paintings produced by Yiadom-Boakye in her exhibition, ‘Fly in League with The Night’ (18 November 2020 – 31 May 2021).

Condor and the Mole by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye (2011)

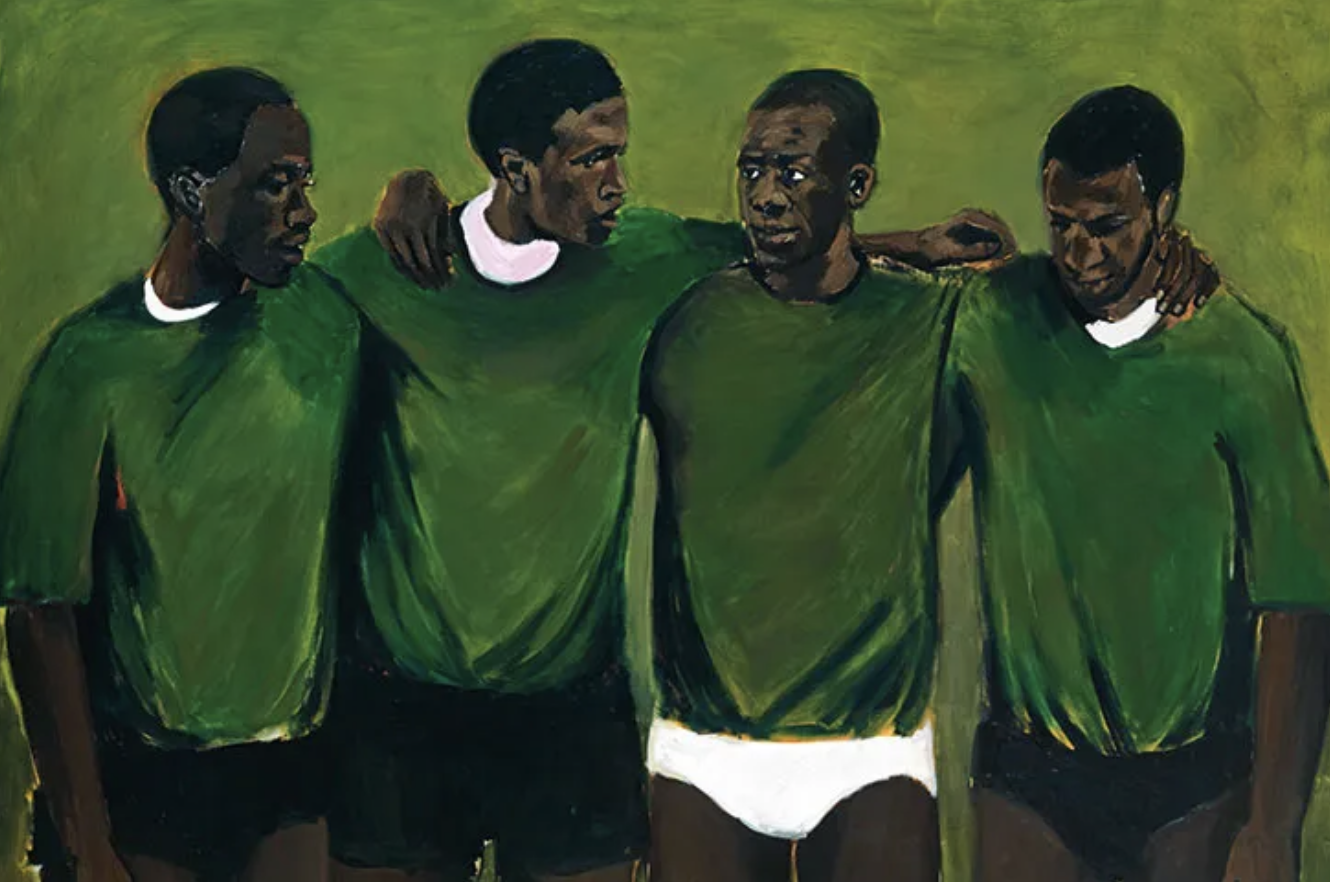

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye is a British painter and writer, who fuses both of these disciplines together and produces paintings which mirror the language of cinematic film stills. This is evident through her particular use of colour and the way in which she represents the people in each artwork. The paintings in the gallery space represent an array of black characters - young, old, feminine and masculine. Upon first glance, one would think that these are people who are from Yiadom-Boakye’s everyday life, but in fact, it’s the opposite. All of the figures are fictitious and are characters who Yiadom-Boakye has amalgamated for our entertainment, as a script writer or film director would do. Each painting stands alongside a title, which is poetic, and adds a secondary layer to the story, that she narrates through her painting techniques.

Within each painting there is a sense of time and pace depicted through the way in which Yiadom-Boakye introduces the characters through oil paint. The scenes are represented in the midst of an incomplete canvas, where the residue of the linen material is evident on the outer corners, while the centre is heavily detailed with paint. This creates a sense of awareness between the subject’s existence as temporary and an act of fiction. Alongside this, she captures an essence of the light and space of each setting, through gestural strokes and a slight application of the oil paint.

However, some strokes are heavier, and reflect the weight associated with the moment that she depicts. Each stroke of paint is subsequently carving out an impression of the exhibition’s story, and creating a feeling surrounding the character and their mood. The overall curation of the gallery space is inviting, as each room offers an alternative stage of the ‘film’ – some paintings, purposefully moody and others joyous and contemplative. Interestingly, when looking at the paintings from a distance, you can see the different character’s faces clearly. But when you step closer, their faces dissolve into colour and mere line work. This is another moment which conveys the surrealistic undertone of Yiadom-Boakye’s way of seeing.

One painting in particular stuck out to me as it reminded me of the film Moonlight (2016) directed by Barry Jenkins. Yiadom-Boakye’s representation of masculinity is soft, intimate, and youthful in her painting, ‘No Need Of Speech’ (2018). The particular relationship between the film and the painting was through the use of the tranquil blue, contrasting effect of colour, and the dramatic focus towards two young black males that are sharing a moment of introspection and stillness as they look at one another.

In Jenkins’ film Moonlight (2016), (which, if you haven’t seen already, you must see, for a number of reasons), Jenkins’ subversively frames a representation of black homosexuality. In the midst of a challenging cultural environment, Jenkins creates space for the pressures surrounding toxic masculinity to be seen through an intimate and tactile gaze. It is therefore interesting to consider the mirroring between Yiadom-Boakye’s paintings and how they speak to a wider language of film culture. This creates a kinetic space for the representation of black identity to be seen in newer, rawer and authentic forms across art.

It’s worth mentioning that, as a black artist, the theme of race and identity inevitably enters the discourse of art, when discussed by critics. This is often something that some artists are opposed to, because they aren’t consciously feeling the need to define their existence for others. Yiadom-Boakye supports this view, stating: “Blackness has never been other to me. Therefore, I’ve never felt the need to explain its presence in the world any more than I’ve felt the need to explain my presence in the world, however I’m often asked.” This reiterates the pressure that artists of black identity have to endure in order to define their existence within the art world. Shifting this way of seeing, Yiadom-Boakye explains that: “I’ve never liked being told who I am, how I should speak, what to think and how to think.” Evidently, Yiadom-Boakye is an independent thinker and this is emphasised through her elicit, evocative, and enticing representation of black people, where she creates her own language and way of seeing her black identity which holds familiarity to what she inherently knows.

So, what type of film director would Yiadom-Boakye be if the ‘Fly in League with The Night’ was transformed into a cinema screening? The film would be multidimensional and introduce audiences to a range of characters, experiencing life across different ages, and sharing these intimate moments with the viewer. Through this, the ordinary moments such as; receiving flowers or sitting in a kitchen living space, become transformed into elongated moments of contemplation and self-reflection. What are these characters thinking? What do they think about when they look at me? In some of the paintings the characters are framed looking outside of the canvas, and into the viewer, transforming the painting into a dialogue. The character becomes the lead, and we become submissive to their gaze. This is an extraordinary shift in the space of painting as the figure becomes life-like, and the narrative around their existence starts to transcend the canvas. “I know them! I’ve seen that person before. I’ve sat in that chair. I’ve stood alongside that group of friends,” one might say as they internalise the paintings as part of their everyday reality. Yiadom-Boakye’s film would therefore feel illusionary and transform the viewer into a space of normative life, but with a purposeful impression of moodiness and tonality towards her distinctive ways of seeing.

Be sure to visit her exhibition when galleries re-open to experience this collision of film and art.